The Governance Principal-Agent Problem

Posted: 2024-07-08.

This post discusses why approaches to governance -- including political, corporate, and in blockchain contexts -- seem to universally follow a "principal-agent" structure. This causes the same types of mis-alignment problems in each setting, including poor decisions, corruption, and/or capture. Can we envision forms of governance that avoid this?

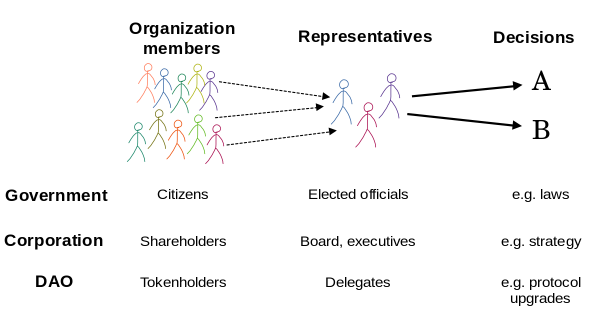

The principal-agent structure of organizations

Let's think about a way that an organization's governance process can evolve:

- Initially or ideally, all decisions are made democratically, e.g. one-person-one-vote.

- But, there are too many decisions; researching them is too time-consuming; and/or deciding is too difficult or requires too much expertise.

- So, we move to some sort of representative democracy. Decisionmakers are appointed via a democratic process. The decisionmakers do the work (labor) of decisionmaking, often in return for compensation (wage).

- But, decisionmakers may have misaligned incentives: what is best for them is not necessarily best for the broader population.

- These misaligned incentives can cause poor decisions (from the standpoint of the organization's entire constituent base). The decision structure is also compatible with bribery, corruption, and feedback loops that consolidate power (capture).

This logic can be applied across different types of organizations, including democratic governments and public corporations.\footnote{Even if their actual history doesn't follow this sequence, I'm suggesting that it does capture the general logic underlying most democracies or corporations.} Recently, many blockchain-based organizations, such as DAOs, are grappling with the same issue while experimenting with new forms of governance. The most common DAO structure today is to issue tokens on a blockchain with a one-token-one-vote democratic decisionmaking process.\footnote{There are two common types of decisions. First is a change to a protocol, i.e. an update to a smart contract's code. For example, Uniswap tokenholders may vote whether to change the fee structure on their markets. Second is an investment or other monetary disbursement, generally in the form of "grants" awarded to new projects.} Because decisions are too numerous and time-consuming (for example, reviewing hundreds of grant applications to decide where the DAO will donate money), projects use liquid democracy or "delegated voting": each tokenholder can delegate their tokens' votes to some other tokenholder.

In DAOs, this is resulting in the emergence of professional or semi-professional delegates. Today or in the near future, tokenholders may pay these delegates a salary for their decisionmaking work and may even sign legal contracts with the delegates to represent their interests faithfully.

But like governments and corporate structures, DAOs are also facing incentive-misalignment problems. Criticisms of delegates include mismanagement of money (for a recent headline, see Arbitrum's $200 million gaming grant) and potential for at least the appearance of quid pro quo, as delegates both bring forward proposals and vote on others' proposals.

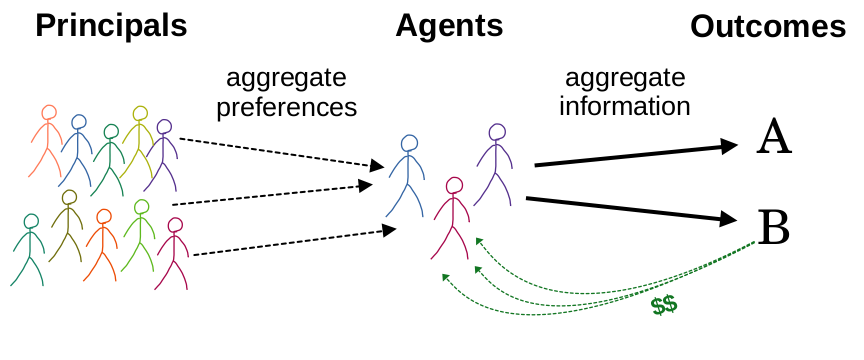

Principal-agent problems

In microeconomics, the principal-agent problem describes a scenario where a principal hires an agent to undertake a project, and the success of the project is observable, but the effort level or decisionmaking process of the agent is opaque. This leads to a potential for misaligned incentives where the principal wants the project to succeed, but the agent does not immediately benefit from exerting higher effort.

In governance, the problem is even worse: the agent could have external reasons for making certain decisions. I highlight three kinds of problems:

- Individual misalignment: The incentives for success within the organization are not aligned with the organization's goals. For example, achieving promotion in a company may be more about networking and making flashy new product launches than about ensuring success of one's existing responsibilities (not to point fingers at any one particular search and advertising giant). In a democracy, re-election may be based on political manuevering that leads to bad outcomes overall. Roughly, these are the same types of misincentives studied in the principal-agent problem, as there are not "external" incentives in this case.

- Corruption: Individual decisions benefit the decisionmaker, but go against the organization's goals. For example, maybe the agent is deciding whether to award a grant, but the agent also works for the company that would get the grant (in DAOs, this is currently very possible). We can try to prevent such cases with rules or laws, but in general the incentive to bribe decisionmakers is always present, and the bribe can usually be much larger than the decisionmaker's wage.

- Capture: A feedback loop that consolidates decisionmaking power in a group that is not aligned with the organization's goals. For example:

Information versus preference aggregation

Consider two paradigms for group decisionmaking: aggregation of information versus aggregation of preferences. Information aggregation is like a group discussion with a goal of reaching consensus about the best course of action. Preference aggregation is like a vote that attempts to find a compromise or otherwise neutral resolution for differing tastes.

Most decisionmaking processes actually involve both types of aggregation, of course. But it's much more common to see formalized mechanisms for preference aggregation: voting, or monetary mechanisms like auctions.\footnote{For example, a single-item auction can be viewed as a way to combine preferences about who should get the item into a final decision. This is a perspective discussed by Vickrey.} In the framework I give above, preference aggregation is primarily achieved by selecting representatives. Information aggregation is the task of the representatives themselves. It is work, i.e. labor: it may involve lengthy research and/or require domain expertise. This information aggregation task, which is not very observable by the principals, is the location of possible misaligned incentives, undue influence, or corruption in the decisionmaking process.

Regarding solutions

The main approach to principal-agent problems is to try to align the incentives of the agents (here, the decisionmakers), so that they make more money if their decisions turn out to be successful. Instead of just viewing agents as laborers --- paid to put in effort to discover and make good decisions --- this approach attempts to align decisionmakers as essentially part-owners of the organization again.

For example, in corporate settings, we see major stock incentives for employees, especially (but not only) for top-level decisionmakers. The idea is that bad decisions will hurt the stock price, so owning stock or options helps align incentives with what is good for the company (more specifically, the shareholders). In blockchain settings, Buterin's Votes as Buy Orders proposal falls along similar lines, suggesting that when delegates in a DAO vote for a decision, they should be automatically invested in the DAO token's resulting price movement.

Unfortunately, there is a major problem. The scope of mis-incentives for a decisionmaker can be much larger than the labor-wage they would typically be paid for their work. A politician making $100-200k might control the awarding of contracts worth $100-200M. The same issue arises, at least potentially, in the corporate and DAO settings. For the incentive-alignment approach to work, the incentives for success might theoretically need to be on the same massive order, an infeasible solution.

This raises the question of whether we should abandon the principal-agent approach to governance and do something else instead. The main proposal I know of along these lines is Hanson's futarchy. There, prediction markets are used to aggregate information about which decision is better, and then the predicted-best decision is made automatically. I have a project proposing a mechanism (we call it SQUAP) using some similar ideas.

In any governance system, we typically want to measure or evaluate the success of decisions. In the principal-agent model, often this is a qualitative evaluation that leads to a choice of whether to re-hire or re-elect the decisionmakers. In futarchy, success is assumed to be fully quantified by some target measure, which we base the decision on. For example, we can use the future share price (or market cap) of a corporation, or token price of a DAO, as a measure of success. The same measure of success is implicitly used in corporations with stock or stock-option incentives. Any governance system, but especially one that tries to escape the principal-agent approach, should probably also be based around some measure of success.

Closing

It would be great to see additional ideas for governance systems that directly address the principal-agent problem. My project "SQUAP" mentioned above uses a monetary mechanism for decisionmaking, based on quadratic voting. In brief, the more you pay, the more influence you have on the outcome. While this is obviously problematic in a lot of political governance contexts, one take-away idea is removing decisionmakers but "allowing" corruption. If a contractor really wants to win a bid, they might pay a significant amount to influence the vote on awarding the bid. That's probably not good, but at least the upside is that the organization is collecting that payment as revenue during the vote (unlike in a corrupt process where the payment goes directly to the decisionmakers). So principal-agent misalignment may be avoided here, even if corruption isn't entirely avoided.

Similarly, we can hope for avoiding capture in the long run by redistribution. If one wealthy interest is using money to influence decisions, but the mechanism can actually collect that money and then redistribute it to members, one might hope that the organization is more resistant to capture. As the influence-money flows in, the organization members get comparatively richer while the corrupting influence gets comparatively poorer, and perhaps power evens out over time. While I doubt we've found the one true solution to capture resistance, I hope this idea can inspire more thought, discussion, and governance proposals.