Economics of Data: Ownership vs Rights

Posted: 2019-04-23.

What does it mean to "own" personal or private data? How should this impact thinking on economics and regulation around data privacy? This post will argue for data rights, not data ownership, and compare to existing paradigms of physical items and copyrights.

Background: Techlash

Recently, there's been a lot of scrutiny and backlash around tech companies and use of private data.\footnote{I'm told by the cool kids that the term "techlash" has been coined for this phenomenon.} Companies\footnote{Such as, but not limited to: Facebook, Google, and advertising networks monitoring behavior on websites; the same and others monitoring location data, often thanks to mobile phone apps; and makers of so-called smart devices such as televisions, even software in cars.} pull in large amounts of user data without explicit permission or compensation. This is seen as a problem and laws such as Europe's GDPR\footnote{https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Data_Protection_Regulation} are being formulated to address it.

One place to center the debate is around who gets to "own" what data. This question has economic, ethical, and philosophical angles. Personally, microeconomics is a large part of my research\footnote{Whereas ethics is more of a side hobby. (And philosophy is over my head entirely.)}, so I'll try to approach it from that perspective.

Before we can get into the interesting economics of personal data (mostly in future posts), we need to step back and ask: What does it mean to "own" personal data?

The Meaning of Ownership

Well, what does it mean to "own" anything? Often, ownership is conflated with "possession". But I think the more general answer is:

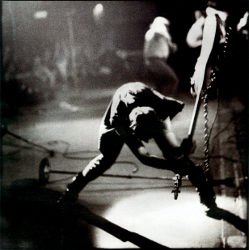

You own your guitar because you get to control what happens to it, who plays it, etc. If you want to smash it onstage, that's your right (as long as the flying pieces don't hurt anyone\footnote{Legal ownership has limitations, of course: owning a car means you have some control over where it is driven, by whom, and how, but it doesn't give you the right to drive it against traffic or without a license.}).

Legal frameworks around ownership of physical items enforce obvious physical realities around control. For example, if I steal your guitar, you no longer have it, so I've clearly deprived you of your ownership rights (for instance, you can't control whether it is used to play Wonderwall).

You can sell the guitar, transferring all rights of control to the new owner. You can also rent the guitar, signing a contract that gives away certain control for a limited duration.

How Do You Own Data?

Take the example of your location data for the past day: where you were at each moment.

If you have this information stored in a data file, then you aren't deprived of it if some company also has that information. (You might not even be aware they have it.) If you sell a copy of the data to someone, you don't necessarily lose it; you could still sell another copy to someone else.

In this sense, "ownership" of data functions like copyright. Data is information. Control over information doesn't follow from natural physical laws the way control over physical goods does. So it is up to legal frameworks to define the kinds of control that can be exerted and by whom.

In the case of copyright, the holder of a copyright (e.g. me or Lady Gaga or Warner Bros.) is given legal control over other people's use of certain information. For instance, it might be illegal for you to sell copies of that information (song or article).

Under copyright, one can buy and sell the "ownership" of the information in the sense of control. If I buy all rights to the song "Alejandro"\footnote{Someday, my loyal readers. Someday.} then I now get to decide who sings it and who doesn't.

But one can do more interesting things too, like sell or rent certain kinds of rights (cede certain kinds of control). Lady Gaga might sell me a license to perform "Alejandro" in New York subway stations\footnote{An important first step.} or so on, without giving me any additional rights.

From this perspective, privacy laws such as GDPR are somewhat strange, or at least limited. They put controls over what kinds of data a company can collect, store, and use. However, they seem to accept that these are non-monetary transactions.

I'm not sure they cover, for example, use of personal medical data for research. If a company wants your records for a study, how should your permission be sought and should you be compensated?\footnote{In my understanding, currently doctors with access to your medical records can use them as part of large-scale studies without informing you, as long as the data is "anonymized" in certain ways. See e.g. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1874535/.} (I note that they do cover some kinds of control that users can exert over collected data, as do "right to be forgotten" laws.)

Without more explicit models around control, they also can't cover cases where a company might like to obtain personal data in order to accomplish a task better (e.g. target ads, identify faces in photographs), but these are not necessary to use of the service. In this case it might make sense for the company to offer to pay users for rights to use this data in these ways.

Data Rights

Therefore, data ownership (evoking "possession") is the wrong paradigm, and the idea of e.g. "paying users for their data" is not nuanced enough. Data is not a commodity, it is information.

Instead, one can picture establishing data rights laws that give users control over how their data is collected and used, along with ability to sign contracts ceding certain kinds of control in exchange for money.

This would be a broader approach to privacy than e.g. GDPR, and it would be more similar to copyright. A person could sell licenses to use her personal data in strictly limited ways and for limited time frames. For example, she could sell Facebook a yearly license to her facial information and photographs. If Facebook wants to keep using them after a year, they have to renew the contract.\footnote{I'm not claiming to foresee how to make this practical. In fact I'm not even claiming yet, in this article, that it's a good idea to do at all. I'm just claiming that, from an economic perspective, the concept of data ownership (as in possession) doesn't make sense, while data rights do.}

While this could function similarly to copyright, there could also be interesting differences. For example, copyright is automatically granted to a creative work upon creation; do private data rights work the same way (and what data counts as private)? And, while Lady Gaga can legally sell me all her copyrights to "Alejandro" (or her label can), perhaps it would be legally impossible to give up all control over one's own data.\footnote{Just as it is legally impossible to give up certain rights in exchange for money (sell oneself into slavery).} While one can resell copyrights, perhaps it would not be possible to grant companies the ability to "resell" one's private data -- any future user of your data must purchase the rights from you directly (or your designated data broker).

Some Challenges

Instead of location data, let's consider your DNA genome sequence. The challenge in this example is that this contains personal information also of your parents, siblings, and other relatives. To what extent do you have the right to cede this information (or control over it) when it is their personal data too?

Another example: Suppose you take a selfie in Central Park, and I happen to be running by in the background. The (timestamped) image potentially contains sensitive personal information about me, such as my face, location, and favorite brand of running shoe\footnote{If any.}. Do I get to exert any control over how you use or share that image (for which you hold the copyright)?

A more pragmatic challenge is the potential for misuse of such laws. Many are concerned that copyright laws in the United States have become far more advanced in scope than their original intent. This (they might argue) results in censorship and unequal power concentration in companies (e.g. ability to take down videos on YouTube more or less on a whim via ContentID).\footnote{https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/11/18220032/youtube-copystrike-blackmail-three-strikes-copyright-violation, https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2016/02/29/youtube-alters-response-to-takedown-complaints/, https://theweek.com/articles/608700/copyright-laws-are-breaking-youtube-heres-how-fix-problem, https://torrentfreak.com/vox-targets-the-verge-critic-with-dubious-youtube-takedown-190215/.} The same concerns might apply to data rights laws. One could picture, for instance, a malicious user repeatedly uploading other people's personal data to a social media or Web 2.0 site such as Wikipedia, StackOverflow, Reddit, etc., then using data rights laws to land these sites in legal trouble. One could also picture misuse for censorship purposes. (This problem has been raised in the past with Europe's "right to be forgotten" laws.\footnote{https://www.wired.com/2014/07/google-right-to-be-forgotten-censorship-is-an-unforgettable-fiasco/})

Arguments For/Against Data Rights Laws

While this post is arguing that legal ownership of personal data should be pictured as "data rights", I'm not actually going as far as arguing that such laws would be a good idea. There are both potential pros and cons.

Here are some arguments I can picture both in favor and against. I'm not going to make the case for these arguments, just list them.

(1) One might argue that people have an inherent, inalienable right to privacy, and this is being violated currently by companies (to say nothing of governments, but that's a different story). On ethical grounds, laws should protect privacy.

(2) One might argue that companies are currently exploiting people's private data for large profits, and that it is only fair and just that average people get a slice of the financial pie. (Others might argue that free services offered such as Google Maps, Facebook's social network, etc. already share value fairly.)

(3) In a very capitalist sense, one might argue that personal data is a valuable resource and has value to people, so someone should own it and we should create markets for/around it. These will create value for everyone. [This is very similar to #2, but in the U.S. you might picture them coming from opposite ends of what they call the "political spectrum".]

(4) From a libertarian or individualist perspective, one might argue that governments should avoid making laws that limit and restrict people's rights, and especially laws that allow other people or companies to do so. In this case, the argument goes that I could take a photo in the park, or simply write down some demographic information of people who walk into my store, then suddenly they have legal power over what I can do with that photo or that information. This might be viewed as a violation of individual freedom.

(5) From a more hippy perspective, one who is against current copyright overreach might also argue that "information wants to be free" and legal restrictions on the flow of information is nonsensical. This argument would say that people should keep information they want private hidden, or only disclose is using existing legal contracts and frameworks to enforce privacy of the other party; but that information once released to the world should be beyond government control. [Again this is similar to #4 although the stereotypical sources of each argument might seem very different.]

(Again, I'm not making these arguments, just brainstorming them.)

Summary

- Data "ownership" really means legal frameworks around control over uses of personal data.

- Data rights are most similar to copyright, not physical ownership.

- Future data rights laws could allow you to sell companies a limited-time right to store or use your personal data for limited purposes.

- The possibilities for data rights could diverge from copyright in interesting ways.

- This will also raise unique challenges in defining personal information.

- There can be arguments why such laws are a good idea sa well as a bad one.

In the next post in this series, we'll talk about how such frameworks might treat data as "capital" versus products of labor and why it might matter. Stay tuned!